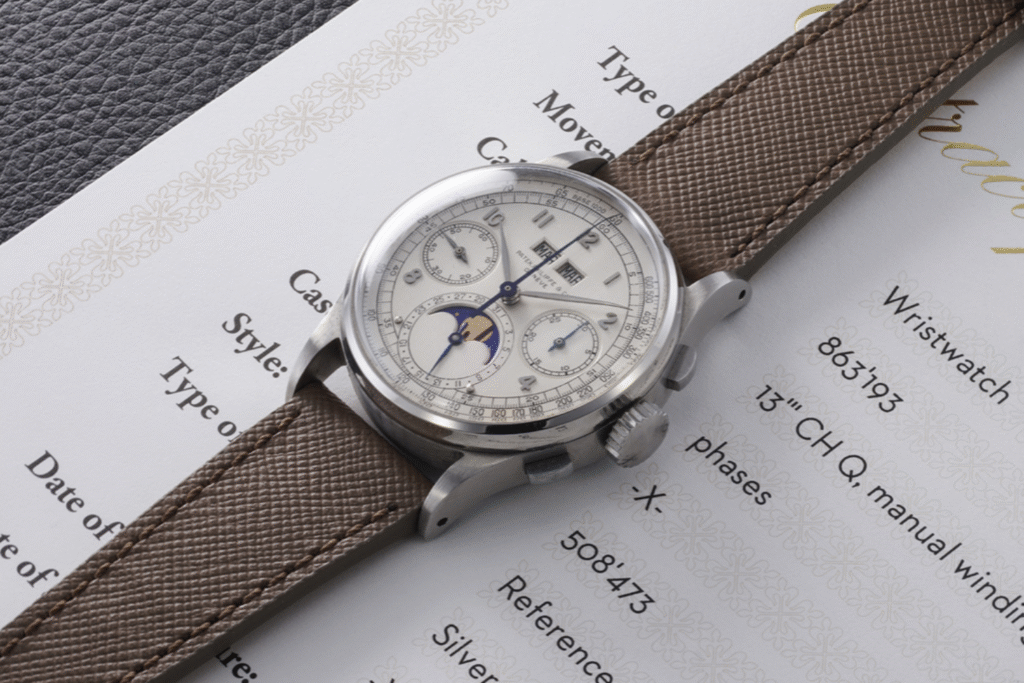

The seed of this reflection was planted in Geneva, when Phillips brought to auction one of the most anticipated watches in the past years: a stainless-steel reference 1518. For almost two months, after the news broke the social medias, the watch world had been humming with expectation.

Collectors and enthusiasts agreed on one thing: a record felt inevitable.

The 1518 in steel isn’t simply rare; it’s one of the four known examples of the most legendary reference of Patek.

Rumor had it Monaco Legend was offering another privately around 20 million euros, which only reinforced the expectation that Phillips’ example would sit comfortably in that orbit.

Rarity mattered. Condition mattered. But what mattered most, and this is where the story begins, were the people, the narrative, the perception.

The perception

Phillips is, at present, the lighthouse of the auction world. A sale under their hammer carries cultural weight beyond the estimate printed in the catalogue. Yet in the weeks leading up to the auction, something shifted.

Perezcope, arguably one of the most influential voices operating within the digital watch space, released a series of analyses highlighting discrepancies and microscopic details that raised questions. Side-by-side comparisons with the other steel 1518 on sale brought attention to nuances nearly invisible to the naked eye. And nuance, today, is everything.

To be clear, this was a phenomenal watch. A 1940s survivor in extraordinary condition, exceptional in every absolute sense. But we live in an era where “phenomenal” is not always enough to break records. When images can be magnified to the last megapixel, when collectors can scrutinize the bevel of a lug or the serif of a font in 8K resolution from their phone, the margin for consensus narrows to a razor’s edge. The difference between a world record and almost a world record may come down to a handful of magnified millimeters, or more accurately, to whether the community agrees those millimeters are flawless.

The result showed it clearly: beauty, rarity, and provenance are necessary but no longer sufficient. A watch must also be approved, indirectly, collectively, almost ceremonially, by the network of voices that shapes contemporary connoisseurship.

And here lies the heart of the argument.

In today’s market, an auction result is not merely the reflection of an object, but of a conversation.

Approval in modern watchmaking collecting

We see the same psychology at play in modern steel Rolex. Why do these watches perform as they do, even when some argue they lack the romantic, artisanal irregularity of vintage production? Because they have become socially verified. Their value is not just perceived individually, it is reaffirmed communally. We feel safer, even justified, buying what we know others admire.

A Submariner is not merely a watch, it is a shared symbol, a recognized token of taste, a purchase cushioned by a collective nod.

Collecting has always involved passion, connoisseurship, emotion. But what is shifting is the calibration of value itself. The market is scaling: more collectors, more information, more scrutiny, more conversation. That conversation now has measurable financial consequence.

Three decades ago, auction catalogues offered sparse descriptions and sometimes a black and white image.

Today, they resemble scientific dossiers, macro photography, ultraviolet scans, serial-block mapping. The audience demands it. The market rewards it. The final percentages separating one exemplary piece from another grow smaller, but infinitely more valuable.

The future of watch collecting may not be defined solely by how beautiful or rare an object is, but by how universally its quality is recognized.

Because in this new era of horology, a watch does not achieve greatness when it is merely exceptional, but when the community agrees that it is.

Follow us on our social media channels to stay up to date with the latest news from the world of watchmaking, and discover what’s new on Watchype.